|

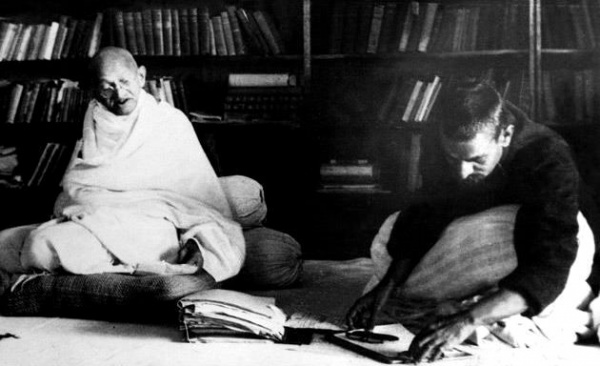

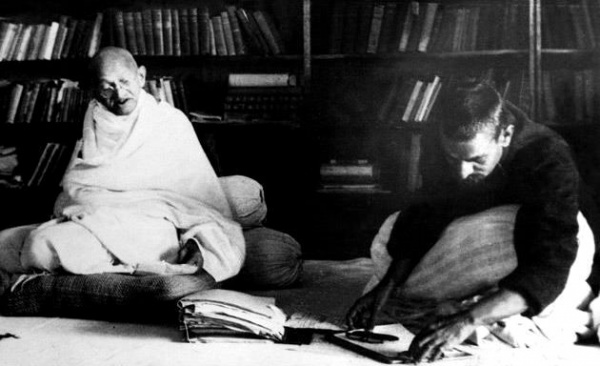

We feature excerpts by Gandhi that lend insight into his values and personal practices.

For him, it was clear that the status quo of inequality and oppression had its foundation in an education out of context of the Indian roots and culture. Gandhi "did not believe in the existing system of education, and he had a mind to find out by experience and experiments." For him true education was more like fostering kinship. As he lived and taught at the Tolstoy Farm, he even tried to be the young people's father, twenty-four hours of the day!

In the excerpt below, Gandhi lays down some of his views on education.

Head, Heart & Hands: Balanced Education Cannot Be Imparted Through Books (Sep 09, 1921)

So many strange things have been said about my views on national education, that it would perhaps not be out of place to formulate them before the public. In my opinion the existing system of education is defective, apart from its association with an utterly unjust Government, in three most important matters:

1. It is based upon foreign culture to the almost entire exclusion of indigenous culture.

2. It ignores the culture of the heart and the hand, and confines itself simply to the head.

3. Real education is impossible through a foreign medium.

Let us examine the three defects. Almost from the commencement, the text-books deal, not with things the boys and the girls have always to deal with in their homes, but things to which they are perfect strangers. It is not through the text-books, that a lad learns what is right and what is wrong in the home life. He is never taught to have any pride in his surroundings. The higher he goes, the farther he is removed from his home, so that at the end of his education he becomes estranged from his surroundings. He feels no poetry about the home life. The village scenes are all a sealed book to him. His own civilization is presented to him as imbecile, barbarous, superstitious and useless for all practical purposes. His education is calculated to wean him from this traditional culture. And if the mass of educated youths are not entirely denationalised, it is because the ancient culture is too deeply embedded in them to be altogether uprooted even by an education adverse to its growth. If I had my way, I would certainly destroy the majority of the present text-books and cause to be written text-books which have a bearing on and correspondence with the home life, so that a boy as he learns may react upon his immediate surroundings.

Secondly, whatever may be true of other countries, in India at any rate where more than eighty per cent of the population is agricultural and another ten per cent industrial, it is a crime to make education merely literary and to unfit boys and girls for manual work in after-life. Indeed I hold that as the larger part of our time is devoted to labour for earning our bread, our children must from their infancy be taught the dignity of such labour. Our children should not be so taught as to despise labour. There is no reason, why a peasant’s son after having gone to a school should become useless as he does become as agricultural labourer. It is a sad thing that our schoolboys look upon manual labour with disfavour, if not contempt. Moreover, in India, if we expect, as we must, every boy and girl of school-going age to attend public schools, we have not the means to finance education in accordance with the existing style, nor are millions of parents able to pay the fees that are at present imposed. Education to be universal must therefore be free. [...]

The introduction of manual training will serve a double purpose in a poor country like ours. It will pay for the education of our children and teach them an occupation on which they can fall back in after-life, if they choose, for earning a living. Such a system must make our children self-reliant. Nothing will demoralize the nation so much as that we should learn to despise labour.

One word only as to the education of the heart. I do not believe, that this can be imparted through books. It can only be done through the living touch of the teacher. And, who are the teachers in the primary and even secondary schools? Are they men and women of faith and character? Have they themselves received the training of the heart ? Are they even expected to take care of the permanent element in the boys and girls placed under their charge? Is not the method of engaging teachers for lower schools an effective bar against character? Do the teachers get even a living wage? And we know, that the teachers of primary schools are not selected for their patriotism. They only come who cannot find any other employment.

Finally, the medium of instruction. My views on this point are too well known to need re-stating. The foreign medium has caused brain-fag, put an undue strain upon the nerves of our children, made them crammers and imitators, unfitted them for original work and thought, and disabled them for filtrating their learning to the family or the masses. The foreign medium has made our children practically foreigners in their own land. It is the greatest tragedy of the existing system. The foreign medium has prevented the growth of our vernaculars. If I had the powers of a despot, I would today stop the tuition of our boys and girls through a foreign medium, and require all the teachers and professors on pain of dismissal to introduce the change forthwith. I would not wait for the preparation of text-books. They will follow the change. It is an evil that needs a summary remedy.

My uncompromising opposition to the foreign medium has resulted in an unwarranted charge being levelled against me of being hostile to foreign culture or the learning of the English language. No reader of Young India could have missed the statement often made by me in these pages, that I regard English as the language of international commerce and diplomacy and therefore consider its knowledge on the part of some of us as essential. As it Contains some of the richest treasures of thought and literature, I would certainly encourage its careful study among those who have linguistic talents and expect them to translate those treasures for the nation in its vernaculars.

Nothing can be farther from my thought than that we should become exclusive or erect barriers. But I do respectfully contend, that an appreciation of other cultures can fitly follow, never precede an appreciation and assimilation of our own. It is my firm opinion, that no culture has treasures so rich as ours has. We have not known it, we have been made even to deprecate its study and deprecate its value. We have almost ceased to live it. An academic Grasp without practice behind it is like an embalmed corpse, perhaps lovely to look at but nothing to inspire or ennoble. My religion forbids me to belittle or disregard other cultures, as it insists under pain of civil suicide upon imbibing and living my own.

Source:

CWMG, Vol 24, p. 155-158, Young India, September 1st, 1921

Be the Change: This week support (a movement of) teachers who stress the importance of the culture of the heart and indigenous roots.

|