Poetry Of Medicine: Lessons From A Revolutionary

epitaph # 1

tell them

i stood

side by side

the doctors and the dreamers

a poem in my left hand

a scalpel in the right

tried and tried to funnel

lillies and light

from poems

into the tip of my scalpel

cut a slice of bread

for the hungry

i stood

side by side

the doctors and the dreamers

a poem in my left hand

a scalpel in the right

tried and tried to funnel

lillies and light

from poems

into the tip of my scalpel

cut a slice of bread

for the hungry

-Elsrizee

“When people ask me what kind of doctor Sri is, the reflex answer that comes up for me is: the good kind,” Pavi opens.

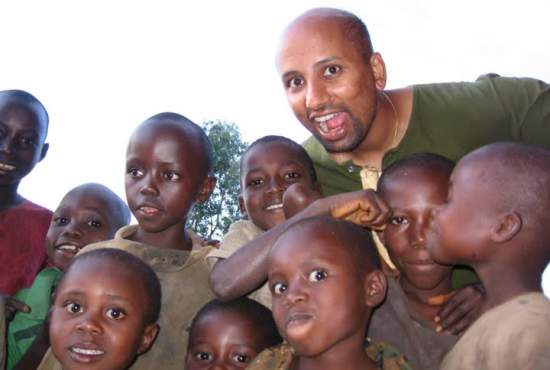

Five months of each year, he lives and works in some of the world’s poorest regions. He walks his talk into Tanzania, Burundi, Guatemala, Rwanda, India and Nepal. After the earthquake in Haiti, he was one of first doctors to fly to the devastated nation. With fierce conviction and soft compassion, Dr. Sriram Shamasunder is a steady force of hope, beauty, and truth in the world. With striking humility and shattering sincerity, he shares the poetry of his journey through medicine, global health, writing, and beyond during last Saturday's Forest Call.

A Slight Taste of Truth

“What is it that drives you out of sunny California, the luxuries and comforts of the Bay Area?” asks Pavi.

He replies with a firm softness of tone, in an answer that cuts to the very core: “It’s almost like the Matrix, where you take the red pill or the blue pill. Once you have the slight taste of truth or reality, there’s no other choice in the matter.”

One of these early tastes of truth hit Sri when he was twenty-four. A fourth-year medical student at the time, he finds himself a few hours outside Bangalore, India, in a Tibetan refugee camp set up by the Dalai Lama. At every turn, people cough up blood. A tuberculosis outbreak had spread across the community, and there were no doctors, no formal healthcare system to address it.

Overwhelmed with the reality of people dying around him, and having been schooled in the epidemic’s causes and cures, Sri’s heart tugged at him to do something. With no formal training or certification, he began to see patients. One by one, monks and nuns lined up for his counsel. As he saw them, an ethical dilemma brewed inside: “I’m not even trained.” Could he really be doing this? As these questions stewed, he was faced with sixty to seventy nuns waiting in a line. Sick, seeking treatment, and waiting for him. Sri was just a student, not yet a doctor. But there was no one else. The ethical dilemma took on a new question: How could he not?

In this early experience at the refugee camp, Sri was struck by how needless the deaths were. The treatments “don’t take rocket-science physicians. They just take a little bit of knowledge and a little bit of generosity and humane systems… They’re dying of things that we have been able to treat for generations,” he recalled. “You just see the potential to avert so many needless deaths.”

With that small taste of what is possible, the decision has become simple. And Sri hasn't looked back.

“Since some of the early trips of working in India or even Burundi, the question sometimes is: Why do I come back to California?” he laughs.

“Internal” Medicine

Though Sri brushes it all off lightly, there’s a lot of heaviness to this work.

In a field that constantly faces sickness and death, many medical students quickly learn the necessity of self-preservation. Studies show that doctors come out of medical school with less compassion than they go in with. The hardening of emotion has become a part of the training, a defense mechanism to prevent burn-out.

“And then there’s you,” Pavi remarks. From tending gunshot wounds in Los Angeles to serving earthquake survivors in Haiti and children on the brink of starvation in parts of Africa, Sri seems to evade any sort of self-preserving barrier. Personal sacrifices are not one to stop him. Even his mom has been known to joke that if she gets sick, she’ll have to go to Burundi to get treated.

“You’ve for so many years now been staring these rare forms of suffering in the face,” observes Pavi. “And one of the most remarkable qualities about you is that you’ve managed to maintain a soft and open heart through all of it. What keeps that alive?”

“You’ve for so many years now been staring these rare forms of suffering in the face,” observes Pavi. “And one of the most remarkable qualities about you is that you’ve managed to maintain a soft and open heart through all of it. What keeps that alive?”In Burundi, eight or nine young children passed away before his eyes. The treatment was simple—food and fluids. But their malnourished bodies couldn’t absorb any nutrients. One after another they passed on.

“I remember feeling so defeated. There are all these questions. You do end up feeling like you’re not doing enough, you’re almost failing….But what helped me with meditation and even writing is just feeling connected to people outside of your physical space. And realizing that you stand on shoulders of all kinds of people all over the world that have committed to work similar to this.”

Beyond lightening the load of physical pain in the world, there is a spiritual groundedness in the decisions he’s made and the way he approaches the sights and sounds of this path.

“The more I’ve been in different places, you just see amongst people the same human qualities of suffering and compassion,” he describes. “And then you start to recognize it in yourself. For me, I came from initially having a sense of anger at some of the injustices—the needless deaths and suffering—and then moved on to see my own suffering in the process. It’s a level of personal transformation worth doing this work.”

As the journey moves from the inside-out, feelings of defeat and moments of breakthrough become all part of the practice.

“If I myself am scattered, if I myself am feeling depressed and down it becomes not useful to the person in front of you. And the person in front of you may have one month or seventy years to live. If you don’t have that mindfulness, and you don’t connect yourself to thousands of people across the planet that are also doing difficult work, and also are able to maintain a certain amount of equanimity, I think you can get lost.”

On Keeping a Clean Shirt Clean

A solid seeker of truth, Sri met poet/professor/feminist/civil-rights activist June Jordan, when he was about nineteen years old.

“At that time in my life, she just really helped me find my voice,” he explained. “She had this ability to have almost a righteous anger, and cut through all that is right and wrong with the world. But also have a level of tenderness, and gentleness, and compassion.”

A fierce soul of a woman, June had started an unparalleled class at UC Berkeley called Poetry for the People, which pulled students together and inspired them tell their truths through the medium of poetry. Using language to cut through falsities, the class brought students in touch with themselves. It transformed strangers into community.

A fierce soul of a woman, June had started an unparalleled class at UC Berkeley called Poetry for the People, which pulled students together and inspired them tell their truths through the medium of poetry. Using language to cut through falsities, the class brought students in touch with themselves. It transformed strangers into community.Sri formed a close friendship with June and stayed in touch through the last year of her life. At 65, she was dying of breast cancer. Sri was a first-year medical student in New York. They talked almost every other day. She would share rich stories from her life—of moments from the Sandinista movement or spending time with James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison.

Their friendship was the kind that sliced rays of honest reality in each encounter. Sri recalls:

When she was really close to passing away, she really struggled with the fact that her legacy was out of her hands at some level. I think the class that year had taken a shift in ways that she felt was kind of stepping on what she had stood for, and her memory. I had come to her house after a class that had gone particularly bad, and she was in the throes of chemo and radiation. She was exhausted. …I was wearing a white corta, and I came in the door and started talking to her.

She was close to the end of her life-- she was dying—and a lot of the things she stood for were getting lost. And when I was playing with her dog, her dog jumped on me and stained my white corta. I had a shirt underneath, so I took off the corta and she said, "I'll wash it for you."

I said, “No, no, you’re so sick. What are you talking about? I’ll just take it home.”

But the next class, she brought my white corta back to me and she had written this poem that’s called, It's Hard to Keep a Clean Shirt Clean. It’s about how in the course of our lifetimes, we attempt to do good. We attempt to maintain a certain values and righteousness. And life comes in the way. Things happen.

You can try to keep your clean shirt clean, but it gets muddied. And when you try to clean it again, it’s different.

She ironed it and washed it, and tried to get it to its original self. But life in and of itself—as time passes—takes you on a trajectory where you can’t control everything. And your clean shirt, even if you get it back to being clean, is not the same as it was before it got sullied.

How to Give to a Revolutionary

When you hear Sri share, you’re struck by his honest openness. Nothing feels unsaid. Combine that with his capacity to give, and it’s no surprise that people feel naturally compelled to give to him. But giving to a revolutionary is not so straightforward. :)

At the end of the call, we run a few minutes over. On the last question, the voice of a young child cracks into the phone: “How can I give money?”

“One thing is to make yourself aware,” Sri begins to answer. Then, pick an interest, pair it with a need in the world, and take it from there. But beyond that, it’s the inner-to-outer change—the kind you can’t quantify or measure or even see all the time—that makes all the difference.

“More so than money, it’s about trying to personally transform.” Sri shares the onus with everyone on the call. “This amount of generosity that is accumulated here, those merits do go far and wide. They’ve inspired me tremendously.”

In seeking to give, we receive more along the path than we could ever imagine.

Beautiful lessons, from a resounding revolutionary. One who won’t—who can’t—settle to live any other way.

An American doctor and UCSF Faculty, Dr. Sriram Shamasunder dedicates five months of the year to working abroad in regions of extreme need. He co-founded and co-directs the first ever Global Health-Hospital Medicine Fellowship at UCSF, which aims to train the next cohort of leaders in Global Health delivery and implementation.

Posted by Audrey Lin on May 16, 2012

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

5 Past Reflections

On May 17, 2012 Guri wrote:

Sri, Thank you for all that you do, and sharing these beautiful insights. It has been a joy to witness the unfolding your life. Pavi/Audrey and the Forest Call team ... gratitude to all of you for bring such journeys of everyday heroes to light.

On May 17, 2012 Birju wrote:

deep breath. wow. Sri, the many little sacrifices that you must make in order to live life in this way is absolutely astounding.

On May 21, 2012 Astha wrote:

does anyone possibly have the contact info for Dr. Sri? I am moving to the bay and am going to be graduating residency and would love to collaborate/learn with him.

On May 22, 2012 Chris wrote:

Utterly beautiful. And weren't Pavi and Audrey the perfect ones to package the conversation. The June Jordan story with the shirt, and the poems, oh the poems! They brought tears. Especially her poem... even in her last moments of life she was learning and sharing it artfully. Kinda like you've been doing all along, elsrizee. :)

On May 17, 2012 Bela wrote:

Post Your Reply