Happiness In The Himalayas (and Bhutan)

.jpg)

Ever since I was a kid, I have thought of Himalayas as my home. Now, I was surrounded by them in Bhutan. (Just landing at Paro Airport is an experience, which apparently only eight pilots are qualified for.)

In a country that didn't have TV or Internet till 1999, that still doesn't have any signal lights, and where dogs stay put in the middle of the road because they know cars will swerve around them, Bhutan is closest we might come to Shangri-La. Few decades back, they only allowed 5 thousand visitors per year. Overwhelming majority of its 700 thousand population practice Buddhism. 72% of their land is green cover, 69% are farmers, and they have pledged to be forever carbon neutral. Everyone has free medical care, can study for free, and no one in the country goes hungry. In 2008, the King voluntarily gave up power to spawn a democracy.

In a country that didn't have TV or Internet till 1999, that still doesn't have any signal lights, and where dogs stay put in the middle of the road because they know cars will swerve around them, Bhutan is closest we might come to Shangri-La. Few decades back, they only allowed 5 thousand visitors per year. Overwhelming majority of its 700 thousand population practice Buddhism. 72% of their land is green cover, 69% are farmers, and they have pledged to be forever carbon neutral. Everyone has free medical care, can study for free, and no one in the country goes hungry. In 2008, the King voluntarily gave up power to spawn a democracy.

Gross National Happiness (GNH) is perhaps what they’re globally best known for, today. In fact, it was the GNH Center that hosted our group. The former prime-minister Jigme Thinley shared the back story: “When he was sixteen years old, the fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, roamed around the country and asked people what they really wanted. It turned to be happiness. Development with values was how our King described it in 1972, when we started GNH.” The idea to aim for a more holistic well-being, one that goes beyond economic development. If you were to ask the King, though, he might just cite the 1729 legal code of Bhutan that explicitly penned: “If the Government cannot create happiness (dekid) for its people, there is no purpose for the Government to exist.”

The intention of GNH is broadly appealing: “The transformation towards a different vision for development begins with the recognition of the complexity and interrelatedness of human reality. The principles of this new paradigm are: 1) transformation in what we value; 2) reconsideration of the purpose of development; 3) re-orientation of humanity towards service; 4) recognition of our interconnectedness; and 5) an ethos of cooperation.” As Bhutan has embraced the GNH Index, a lot of thinking has gone into 9 domains, 33 sectors and 124 variables of societal well-being.

In practice, of course, happiness is complicated. World Happiness Report of 2015 lists Bhutan as 79th happiest country in the world – just about half way through the list, that is usually bested by nordic countries like Norway, Denmark and Switzerland. “Rankings are political,” Jigme Thinley shared with a smile. “It depends on your definitions.” Even within the country, definitions can vary. As the world’s youngest democracy, Bhutan’s current prime minister won the elections on a campaign against GNH. “We’ve had enough talk about happiness, it’s time to build some roads,” one of the locals told me. During a thoughtful panel in city of Thimpu, a leading scholar reflected on a current debate around setting up Bhutan’s first slaughter house: “Economists are saying it’s much cheaper to localize the meat, but Lamas are saying we should not kill.” Despite being a country with 92% Buddhists, where smoking gets you a 3 year jail sentence, alcohol and meat are very common – and the question becomes, “Should we be practical and not import meat, or does localizing it somehow gives us permission to do more of it? In five years after TV and Internet were introduced in Bhutan, for example, crime rate shot up 400%.”

Such difficult questions are coming in from all sides of modernity. Karma Phuntsho, a leading scholar who has written the seminal book on history of Bhutan, flatly told us, “English is the weed that will destroy our culture.” Since 1960’s, all Bhutan schools have adopted English as their primary language. Subsequently, today’s kids often have a tough time communicating with their parents because Dzonghkha (the most common of 20 languages in Bhutan) simply doesn’t have the linguistic constructs to describe some of today’s individualistic struggles – from a child stealing fruits from another child, to defriending someone on Facebook. English is now the most common language in the country and to the chagrin of many, some government officials have even proposed to make it the national language.

Amidst all the debatable content, what I was most deeply struck by was the context of Bhutan and its people.

Everywhere there are prayer wheels, often powered by streams of melted ice flowing down from the mountains. All life, whether a river or an old tree, is said to inhabit a deity – and hence to be held with reverence. A serene sort of beauty pervades all landscapes. Tibetan prayer flags of compassion swing freely in open fields. In the main newspaper, you may well read a story about a viral outbreak at a school, coupled with numbers on how many students went to a Lama for “traditional” healing and how many went to Western hospitals for allopathic medicine, and how the monastic treatment ended up being more successful. In the various interactions with Bhutanese leaders -- from high ranking government officials to internationally educated scholars and leading educators – everyone spoke without a sense of authority, deflected attention, and repeatedly bow with an elegant simplicity. No one felt rushed to impress.

Even the fact that there’s been a weekly Awakin Circle in Thimpu says something. :)

At the end of the beautiful Awakin circle we had (in Paro), Sonam handed me a parting gift -- “Blanky”, a block of wood with some hand-drawn art, that is present at all their Awakin Circles. “Blanky represents all those who couldn’t join in person, but are with us in spirit,” she said before paying it forward to our Awakin Circle in Santa Clara. (They also shared a touching story of how a young student, who used to quietly just sit in on Awakin Circles, committed suicide two weeks back.)

On the whole, all locals seem to understand that the double-edged sword of modernity is upon them, but can Bhutan’s context help broaden our global idea of progress? Bhutan may be 79th on World Happiness Report, but it was Bhutan that inspired that report in the first place. A senior Tibetan monk joked how GNH for locals actually starts in the opposite order: “Happiness within, then Nationally, and then Grossly.” The same Karma Phuntsho, who is worried about preserving Bhutanese language and culture, is now also supporting budding entrepreneurs: “There’s the traditional entrepreneur, who is me-oriented. There’s mediocre entrepreneur who is serving others on the outside. But what we need are Boddhisattva Entrepreneurs who are purifying their mind and serving the world.” (Reminded me of Generosity Entrepreneurs.) In Jigme Thinley’s thoughtful remarks, as a man who actually implemented GNH across Bhutan, I noticed a subtle distinction between the Western ideal of happiness as a blissful destination versus the Bhutanese notion of happiness as state of equanimity that embraces cyclical ups and downs of life.

In so many ways, such invisible details of Bhutan’s wealth have ignited an important global conversation. Whether in UN discussions on development or on talks on upgrading democracy or in speeches by heads of state, well-being and happiness are now commonly heard. Some worry that metricizing happiness will desensitize us to the subjective nuances of well-being, while others point to examples like that of Dan Rice, who read a research paper on well-being and dramatically redistributed salaries at his 120 person company, raising everyone’s minimum salary to $70K while dropping his from a million to $70K! The conversation continues on.

In so many ways, such invisible details of Bhutan’s wealth have ignited an important global conversation. Whether in UN discussions on development or on talks on upgrading democracy or in speeches by heads of state, well-being and happiness are now commonly heard. Some worry that metricizing happiness will desensitize us to the subjective nuances of well-being, while others point to examples like that of Dan Rice, who read a research paper on well-being and dramatically redistributed salaries at his 120 person company, raising everyone’s minimum salary to $70K while dropping his from a million to $70K! The conversation continues on.

As awesome as GNH is, Bhutan’s contextual field feels far far more significant – and powerful – than a particular manifestation. Bhutan’s irrevocable strength is its spirit. They hold life on a very long time horizon, afforded by an active connection to their ancestors and their belief in re-incarnation, and that changes the basic design principle of their society.

In the remote regions of the country, a four year old was said to have run into the Queen, and almost spontaneously started speaking in a language he could’ve never learned there. Rather impressed, the Queen befriended him and ultimately introduced him to the King. When he meets the King, surprisingly, the kid starts scolding him: “You haven’t properly taken care of my monastery, or the dharma.” As the story goes, when the King’s kid-tolerance passes, he instructs him, “You can’t just talk to the King like that!” To that, the kid immediately responds, “Yes, I can. I have been a King long before you.” That four year old is now 22, and it is rumored that the current Je Khenpo (spiritual leader of the Bhutan, akin to the Pope) will name him as a successor, and many are excited about a “spiritual renaissance” in the country.

Such stories can be heard in all parts of the country, only adding to the mystique of an already magnificent landscape.

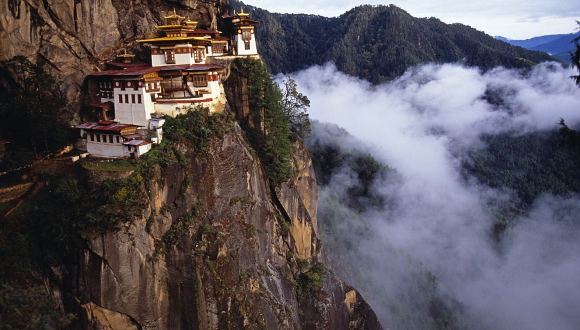

On one of the days, few of us started walking upto Tigers Nest (above) – one of the most holy sites in the country, where an 8th century spiritual master is said to have created a monastery and whose “mandala of vibrations” are still very eminent across the mountain range. Over time, all our paths organically diverged as we found spaces of solitude. I ended up taking an off-the-beaten-path track, and a bit later, I found a secluded rock overlooking the vast, green expanse. After the somewhat strenuous hike, I just sat there quietly, mostly with my eyes closed.

About half an hour in, I remembered a story I had heard at a MBL retreat: “I asked the Boddhisattva if I could make an offering of a meal, and he said he would visit tomorrow. Next day, I prepared a gourmet meal and waited. And waited. No one came. Twice, a dog also came but I shooed him away. A bit disappointed, the next day, I visited the Boddhisattva and sadly asked why he didn’t show. He kindly replied, ‘I did come, but you didn’t recognize me. I was the dog.’”

Just then, a dog shows up to my remote spot. I was flabbergasted. Maybe I subconsciously heard the dog and it made me think of the story, but nonetheless, I will filled with a kind of awe. What was even more remarkable was that the dog came RIGHT next to me, and looked out at the valley, just in the same way I was meditating. For the next half an hour, the dog stayed there, both of us mostly motionless.

As it was time for me to go, I thought that I should make an offering to the dog. I had a packed sandwich and an apple for my lunch, and I laid it there for the dog to eat. He sniffed it, but “No thanks.” :) Then, I wondered, “What else can I give?” I literally had nothing else. But then I remembered my encounter with Dada Vaswani. He had recited a poem by ShantiDeva, cupped both his hands and said, “I seek your tears of compassion.” So I thought to myself, “Ah, maybe I could share my goodwill with this dog.” I sat and prayed that all my merits fall in service to this living being’s journey of awakening. I felt a small of grace, and sure enough, I even teared up. All along, I never had any physical contact with the dog, but sitting there, overlooking the Tiger’s Nest monastery and the trees, I remember a content feeling of gratitude: “I have arrived. I’m so so grateful for having had a taste of life’s most precious jewels. I’m happy to die now. Dear Universe, use me in whatever way I’m needed.”

If I had to describe my experience, I can't pinpoint any particular trigger. It all felt like richly interwoven dance of conditions. Much in the same way, that was my experience of Bhutan -- and Himalayas. I don’t know what about it was extraordinary, but all put together, I felt right at home.

Posted by Nipun Mehta on May 23, 2015

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

18 Past Reflections

On May 23, 2015 Sonam Yangden wrote:

But now, I am changing it to "Blanky" now..I love it! It is so cute!!!! :D

Thank you, so happy to hear about your detailed experiences here in Bhutan.

P.S. - I am still waiting for "Blanky"'s photos! :)

On May 23, 2015 Padmaja Murtinty wrote:

On May 24, 2015 Vinod Eshwer wrote:

On May 24, 2015 Luv4all wrote:

On May 24, 2015 Micky O'Toole wrote:

On May 24, 2015 Hang wrote:

On May 24, 2015 Tim Huang wrote:

On Jul 11, 2015 Danny Newell wrote:

On Jul 12, 2015 Jenn wrote:

On Jul 13, 2015 Kinneri Parekh wrote:

On Jul 16, 2015 Siddhi wrote:

On Sep 2, 2016 Myrna wrote:

Thank you again.

On May 23, 2015 mindyjourney wrote:

Post Your Reply