Mark Dubois: What I Learned From Rivers

Listening to Mark Dubois is like watching the constellations of a night sky light up around you. There’s a quality to his voice that cuts to the core, a delicate balance of humility and strength that unearths a deep surrender, an awed reverence, for existence, the environment, and the rhythms of nature that pulse through the depths of rivers and oceans and, ultimately, our own internal veins.

Fueled by a passion, courage, and inner conviction in our Earth’s majestic ancestry, Mark has devoted life to the preservation and awareness of our planet’s irreplaceable resources. A decades-long familiar face at the forefront of the environmental movement, he’s grown multiple conservation organizations, organized global campaigns to redirect international funds for the planet, and even put his life on the line in 1979 when he chained himself to the bedrock of Stanislaus River Canyon for seven days, as a new reservoir filled.

Yet beyond the checklist of achievements, at the core of what propels Mark is a profound connection to the transcendent tapestry of nature—a realization of the fleeting quality of his life in the grand scheme of things, and a purity of love that manifests through his “legendary” hugs, receptive presence, and ability to “feel life move through him”.

This touching conversation, moderated by poet-doctor Sri Shamasunder and hosted by Anne Veh, unearths the gems from his spectacular journey.

Sri: Where did your love of nature start?

Mark: I grew up in Sacramento, CA, my dad had having bounced all over California in his growing up. So we would often go car camping, to Tahoe, to relatives in Napa, to relatives in the Foothills. And, ultimately, my parents got a little one-room cabin we had to hike in a mile in Trinity county. So all of those weekends connected me to it. And I felt much more comfortable wandering in the beauty of the wild than in my awkwardness in town. It was much easier to be in nature. It was a time for me, and I sense, for all my family.

Sri: Then, in your young twenties, you started this effort to combine that love of nature to bring poor and underserved kids rafting down the Stanislaus River, I believe for free. Can you tell us about that?

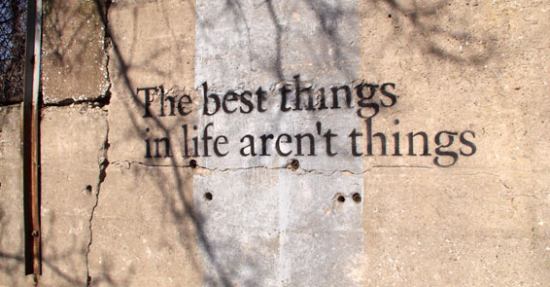

Mark: I worked a couple years as a commercial river guide and just saw the difference the river had made in people’s lives. At the end of one wonderful commercial trip—we just had this extraordinary time—there was this young doctor in his late twenties. I watched him hesitate before jumping into his Porsche to go back to his large San Francisco house. He knew he couldn’t buy the richness of what we had just shared. The less we had the more we had. It was a fascinating experience.

Mark: I worked a couple years as a commercial river guide and just saw the difference the river had made in people’s lives. At the end of one wonderful commercial trip—we just had this extraordinary time—there was this young doctor in his late twenties. I watched him hesitate before jumping into his Porsche to go back to his large San Francisco house. He knew he couldn’t buy the richness of what we had just shared. The less we had the more we had. It was a fascinating experience.

So when a friend had the idea of taking down inner city kids for free, it just landed. We got some old boats donated. Before long we weren’t just doing river trips, we were doing Earth trips. Instead of two-day trips, we were doing five-day trips. We were teaching about the plants and animals and caves. The archeology. The history. The stars. There was not enough time to learn the beauty and the magic that was in this enchanting canyon that just broke open everyone’s hearts and smiles.

Sri: How did you start to connect that love of nature with this larger environmental consciousness of trying to preserve it?

Mark: I had been raised going to dam sites and learning about how important they are for our evolution. But that first caving trip I did probably in 1966 or ’67, the leader pointed down to the canyon and said, “Oh, by the way, they’re going to build a dam on that.” And I looked down and thought, “Oh, that’s too bad. It looks like a beautiful canyon.”

Sri: When you were 28 or 29, you chained yourself to the Stanislaus River Canyon as they were trying to flood it. Why was it worth fighting for that you were ready to essentially die if they were to flood it?

Mark: At some point, we had lost one campaign. And we were going up the river to both mourn our loss and to plan our next campaign. We didn’t have any idea for what to do next. We camped at this place called Razorback. It’s a thousand foot cliff rising vertically over the emerald water. Early the next morning, I walked upstream to this little tiny grapevine gulch that came in. As I had my feet in this just crystal clear water—there was water falling out of the limestone rock, the grapevines were reaching out, the butterflies were dancing across.

In that moment, I just felt life.

And in this just extraordinary feeling, I also had this awareness that if I left the campaign—if I just moved on (our odds seemed overwhelming), I would be very similar to those people in Nazi Germany who had a hint of what they were doing. Because by this time, I had learned that we didn’t need the power. We didn’t need the water. This was the twenty-fourth dam on the river. This was being built on old momentum—it was a good idea before I was born, but it wasn’t a good idea anymore. It didn’t make economic sense. And I knew it didn’t make sense to life.

And in this just extraordinary feeling, I also had this awareness that if I left the campaign—if I just moved on (our odds seemed overwhelming), I would be very similar to those people in Nazi Germany who had a hint of what they were doing. Because by this time, I had learned that we didn’t need the power. We didn’t need the water. This was the twenty-fourth dam on the river. This was being built on old momentum—it was a good idea before I was born, but it wasn’t a good idea anymore. It didn’t make economic sense. And I knew it didn’t make sense to life.

So, at that time, they were dumping dump trucks as big as houses every hour. I was going to start trying to move one rock at a time. I knew it looked feudal, but that’s all that I could think of doing.

Eventually, it came to me that if you are going to flood nine million years of evolution that this canyon has been evolving in, you can take one other critter as well. My life is nothing compared to the miracle and magic that is vibrantly flowing through this place and has been for eons.

Anne: One thing I’ve learned from you, Mark, is that you deeply engage in the relationship with nature. The Stanislaus River has allowed you to fall in love with the rest of the world. And when you have a deep relationship, and a love, there’s no way you can turn your back. That’s how—knowing you, meeting you, and being the recipient of one of your legendary hugs—you feel life move through you.

Mark: Well, thank you. There’s that line that goes, “Be careful what you fall in love with.” [laugher]

At one point, I had the privilege of going down the Grand Canyon with Dave Brower. He was doing talks every other day. The last night, he said, “You know, every resource I’ve talked about is non-renewable. The Earth pays for it. But there’s one resource where the more you give out of it, the more it comes back to you. And that’s love.”

At one point, I had the privilege of going down the Grand Canyon with Dave Brower. He was doing talks every other day. The last night, he said, “You know, every resource I’ve talked about is non-renewable. The Earth pays for it. But there’s one resource where the more you give out of it, the more it comes back to you. And that’s love.”

Sri: Eventually, they ended up flooding the Stanislaus, and you ended up losing that particular struggle. Is it that deep love and connection that allows you to recover? In the face of continuous struggles, how do you maintain that optimism?

Mark: Well, my optimism may wane like the waves as well. A week ago, I did go up to the Stanislaus and I spent five days there. When I floated through the death ring of this reservoir, I found myself thinking of the Toltecs, who would cut out of the living being and hold up this pulsing heart. And I found myself again just feeling this deep cut in the sacred Earth to give us a little more money and power. We just have no connection to where these things come from these days.

In our youthfulness as a species, we don’t often take the time. We get caught in our hamster wheel of all the important, busy things we’re doing, and we forget to tap into the depth of our hearts and our gut and the half of our brain that knows we are much, much more. And we’re intertwined with all the sacred of this miracle.

So people like Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, and Mandela all tapped into this deep knowing of who we truly are and what we are truly capable of. So, for me, my optimism does come from knowing that when we awaken beyond blaming “them”, when we step into really tapping the wealth within us—that it’s not just within us, cause it’s just intertwined with all life.

This is truly the only game in town: the beauty and magic that we all know at our core. We get to learn how to live beyond fear and scarcity, and live in beauty and joy and love. And invite the world to play with us.

Sri: Is there a practice that allows you to see beauty in the face of so much destruction that mankind persists in doing?

Mark: A year and a half ago, I met this remarkable neighbor. She asked if I meditated. I said, “Well, I don’t think so.” And then she outlined four different kinds of meditation, and I said, “Oh, well I do all of those!”

What I sense is that each one of us are such a unique antenna, a pulsating antenna in the world.

For me, I’ve lived my life as an apology, wishing I could be as smart as my friends, or wishing I could be as calm and radiant as a few people in my life. And ultimately, I’ve slowly been relaxing into the realization that, “Oh! I don’t have their skills. I don’t have their talents.” And learning how to slowly honor what my path is. Paying attention to those things—those people, those voices, those quotes that resonate with me—and paying attention to what’s mine to bring, what’s mine to give forward.

In the last three years, a meditation has been to pay attention to how much fear rules my micro-decisions in life. I’m just amazed at these old patterns and habits. I don’t know if I’ll ever transcend these things, but I’m honoring who I’ve been and what these patterns are. And breathing into the fact that I am all these little things, and I’m also much more than all of that.

In the last three years, a meditation has been to pay attention to how much fear rules my micro-decisions in life. I’m just amazed at these old patterns and habits. I don’t know if I’ll ever transcend these things, but I’m honoring who I’ve been and what these patterns are. And breathing into the fact that I am all these little things, and I’m also much more than all of that.

Even if my life is focused on wanting to figure out how we can make a difference now, at this sacred time on our planet, I am drawn to just take a walk or go on a river trip. When I do, I notice that it roots me, grounds me, into remembering the magnitude of what I am a part of.

Sri: I’m a medical doctor and I spend 6 months in East Africa. The first time I was in Burundi, we had this hospital on the top of the hill, and it’s this really beautiful, beautiful location. There are lush mountains as far as the eye can see. But everyday in the hospital, there’s such destitute poverty and malnutrition. In the course of four months, I must have seen 12 or 14 kids die of malnutrition. And I just had lots of frustration, trying to connect the dots between poverty and health and what my role is in it.

I remember being up at 4 am. In that silence of the morning, and the sun rising on a mountaintop, a lot of my anger and questions started to drop away. You do feel this kind of awe connection to so much of nature and a lot of the things you grapple with and questions that arise. I think in that stillness, somehow, it makes a little bit more sense.

Mark: It’s tapping into that stillness which is accessible to us at anytime. It does seem to come at 4 am or in the quiet of nature, and yet it’s accessible anywhere. How do we tap into that?

As you described your anger, I will say I am more and more clear that when I do anything out of fear and scarcity and separateness and anger, then I am more and more profoundly convinced that I am just reinforcing the old paradigm. And as I ever so slowly learn to take actions out of love, whatever that looks like, feels like, then I am beginning to help co-create the world that we’re meant to live into.

Sri: That’s beautiful. Is that advice you would give to a young activist?

Mark: Yes. I’m more and more convinced that it’s an inside job. For me, I've been drawn to the question: How do we grow, deepen, and mature activism?

When I’m fighting “against”, I’m actually just reinforcing. So, how to be able to do an aikido—how to be able to do a Gandhi—an “Oh, we’re not here to fight you, and we are not going away”?

All of our lives, we’re seeking our love affair with the sacred here, even if we’re still trying to find the words to describe this emerging world view. On one level, we’re talking two different languages. The “modern world” is taking everything and converting it into dollars and cents and products. That which our hearts know is our true wealth comes from being connected—connected to all of our neighbors. Those people you saw in Burundi. And to this sacred Earth.

Prakash: As a responsible citizen of this Earth, how can we take responsibility to hold these sacred rivers in their important place?

Mark: To me, each one of us gets to look into and learn our heart’s fine-tuning. We are all so unique. We can learn—there are so many things we can do to lessen our impact to be more conscious. Every penny we spend, we are voting for the world. I vote for the oil company almost everyday. I’m embarrassed to say that. I can hate what the oil companies are doing, but I vote for them when I drive. So how do I be a more conscious consumer?

I’m also aware that, with every breath I take, I can add more fear and scarcity into the world. Or more love. So how do I become more conscious of every breath with everything I spend, with everything I use? When I turn on the faucet, am I aware that it’s connected to some miraculous stream that has dragonflies and wildflowers? And that doesn’t mean to not use water. It just means to be more conscious of where things come from. How do I become more conscious of what I am putting out and what I am taking in?

Ultimately, the most important thing that we can do is to pay attention to what our hearts know.

So little of our culture reinforces paying attention to our own gifts. When I bring my greatest joys with the world’s greatest needs—and as more and more of us do that—the problems we face will start to vaporize. Because we will be living with more integrity, and the power of our hearts’ knowing will start creating more solutions. We’ll be connected to more people and we’ll enjoy taking on that which we get to take on now.

Alyssa: How do you find more people who are open to these ideas?

Mark: The more I learn to live from my heart—the more I let go of all the fears and the scarcity—then it feels like doors open. And that gives me optimism. Because, we, humanity, are craving something our modern language cannot capture. There are two quotes I’m drawn to share.

Robert Bly conveys, "Embedded in the core of every culture’s stories is the quest to connect the vast, vast distance between the head and the heart.” So, on our evolutionary journey, we are all trying to make that connection.

The other quote, “Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love. And then, for a second time, in the history of the world, man will have a discovered fire.”

Sri: That’s a great quote.

Mark: That’s from Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. One of my dearest friends keeps saying, “Mark, that’s magical thinking! What are you talking about?”

But it answers Sri’s earlier question of why do I have optimism. It’s because I have had the privilege of experience of when our hearts align. I’ve had the privilege of experience of aligning with the miracle of nature. And dancing with water. And all of sudden, I am not me. I am dancing with this incredible flow through time and space and the universe.

We’re all drawn to romantic partnerships. And yet there’s this other partnership when we’re all gifting our collective creativity towards really gifting the future. And yet, we’re not living in the future. We’re following our heart’s instincts for what we know now—what is needed at this sacred time of our collective evolution. And what’s ours to do. As we get our egos out of the way and pay attention to that—look out world, here we come.

Deepa: Is there any way to continue connecting with the deeper, inner processes of external activism work?

Mark: For me, every single person is an activist. Because we are activating the world that exists—by everything we purchase, by every action we take. Wherever we put our attention, we are activating the world.

When I was a caver, I noticed that none of the plants were being drawn into the darkness of the cave—they were all craning their vines to reach towards the sun. And I sense that that is true for all of us. We’re all craning towards the light. We all know it. We all feel it. And in our immaturity, our minds have seduced us to how powerful we are. And all our language has trapped us there.

When I was a caver, I noticed that none of the plants were being drawn into the darkness of the cave—they were all craning their vines to reach towards the sun. And I sense that that is true for all of us. We’re all craning towards the light. We all know it. We all feel it. And in our immaturity, our minds have seduced us to how powerful we are. And all our language has trapped us there.

I am profoundly convinced that we are at the cusp of the greatest transformation humanity has ever been in. So, the craving to pay attention to the power of our hearts—we get to engage in those conversations.

We get to ask: Are we doing this out of fear? Or are we doing it out of love?

Sri: I’ve noticed the people who are engaged in service and connected to nature are the most optimistic. A lot of the people I work with constantly stare suffering in the face, but the amount of vibrancy in their step and the buoyancy in their spirit is infectious.

Mark: Yes. That reminds me of a line by Gandhi:

"Service which is rendered without joy helps neither the servant nor the served. But all other pleasures and possessions pale into nothingness before service which is rendered in a spirit of joy.”

Mark  Dubois co-founded Environmental Traveling Companions (ETC) to bring disabled and disadvantaged youth to the great outdoors, as well as Friends of the River and International Rivers Network. A steady advocate for the environment, in 1990 and 2000, he co-coordinated Earth Day's international outreach, events that engaged 200 million people across 184 nations. He's facilitated ten consecutive lobbying efforts at the World Bank and IMF. In 1979, Mark captured national headlines when he chained himself to the bedrock of the Stanislaus River Canyon as a new reservoir filled. While his action forced only a temporary reprieve for the Stanislaus, the growing movement to protect rivers brought a halt to major dam building in the United States.

Dubois co-founded Environmental Traveling Companions (ETC) to bring disabled and disadvantaged youth to the great outdoors, as well as Friends of the River and International Rivers Network. A steady advocate for the environment, in 1990 and 2000, he co-coordinated Earth Day's international outreach, events that engaged 200 million people across 184 nations. He's facilitated ten consecutive lobbying efforts at the World Bank and IMF. In 1979, Mark captured national headlines when he chained himself to the bedrock of the Stanislaus River Canyon as a new reservoir filled. While his action forced only a temporary reprieve for the Stanislaus, the growing movement to protect rivers brought a halt to major dam building in the United States.

Posted by Audrey Lin on Jun 19, 2014

On Jun 19, 2014 Deven P-Shah wrote:

Thank you for this. What stuck me the most about Mark is clarity of his vision and how he is aligning to that while embracing core universal values that are priceless and timeless. It just felt so right listening to it.

I enjoyed your touch with words as well. Your introduction made me surrender to the moment and read rest of your article... :) ... "Listening to Mark Dubois is like watching the constellations of a night sky light up around you. There’s a quality to his voice that cuts to the core, a delicate balance of humility and strength that unearths a deep surrender, an awed reverence, for existence, the environment, and the rhythms of nature that pulse through the depths of rivers and oceans and, ultimately, our own internal veins."

The message of looking for answers inside, following them and compassionately connecting hearts with others resonated so deeply with me.

Gratefully with smiles, Deven

Post Your Reply